‘In Cluedo it is so easy to be sucked into believing everything other players tell you. It is easy to start thinking that the suspect everyone is accusing must be the culprit because it has the opinion of many behind it. In Cluedo we should listen to others, of course. But we should also keep an independent mind. Is it possible that this person knows that the weapon wasn’t really the dumbell? Yes it is. In keeping an independent mind we have the power to challenge what we have been told and analyse it to be sure whether it is true or false’

~ Isabelle, a year 7 student

What dinosaurs are to early primary/elementary schoolers, Ancient Egypt is to early Middle Schoolers. Kids of all ages love the pyramids, exotic locations, accidental discoveries, the exquisite jewellery, mummies and alleged curses. But that can be where the fascination ends- Cool facts. The challenge for educators is to shift the learning from being the sort of study that resides purely in the ‘About’ domain of information, facts, figures and details into an engaging investigation in which critical thinking, synthesizing, problem solving, logic and application are demanded. We have attempted to bring the latter list to bear on the troubled life of Pharaoh Tutankhamun though imaginative play and a liberal application of Cluedo.

Note that in the introduction I did not use this year’s educational buzzword – gamification – but made a definite choice of the word ‘play’ Why? To be blunt, the word gamification is an ugly, ungainly hybrid that trivialises learning into mere entertainment and reduces games to a clever strategy that gets something across- a kind of a sleight of hand approach to learning – (*assumes condescending voice* ‘Guess what kids? You’re learning something and you don’t know that you are! Isn’t that neat?!’) I argue that existing games have validity in themselves. They can help us learn, practice, implement and normalise meaningful life skills as you’ll see below.

Games and play have always played a part in Education and there is no sign of them leaving any time in the foreseeable future. This comprehensive infographic called ‘Gamification in Education’ presents the evolution of educational games. There is, however, a tendency to focus purely on computer games as being the most valuable in this *gulp* gamification revolution (educationrevolutionification?) and neglect some traditional gaming platforms that don’t need a console. Or an iPad, for that matter. Add to that the fad of offering badges for completing tasks (badgification?) and you could be forgiven for believing that 21st century learners are virtual BoyScouts traipsing about the internet collecting patches. (Though many are, but these patches are the ones gamers are downloading for their MMORPGs.)

Where would be be without a CLUEDO?

Existing games can be a great vehicle for learning. With or without badges. Or, again, iPads. Here’s the associative thinking that lead to our choice of Cluedo as not only an initiating task but as a methodology for our investigation of Ancient Egypt.

- When you think of Ancient Egypt you think of pyramids and Tutankhamun.

- And the Mummy’s curse! Cool! Undead mummies lurching… No, Let’s not go there. Distracting.

- How did he die? What killed him? Where did it happen? Was it murder?

- Was it High Priest Aye in the Throneroom with a Canopic Jar?

- Hey that sounds like ‘Mrs Peacock in the Ballroom with the Lead piping!‘

- *Light Bulb moment* Let’s play Cluedo!

So that’s how we started- buying boardgames invented in 1929, not using Black Line Masters, or a Learning Management System that awards badges (though that would be a cool addition) or even iPads. Old Skool. Our aim? To see if the students could reflect on the skills needed to play and wonder if these could be applied elsewhere. After playing a few games in teams we asked them to consider what an historian was and then posed this question – ‘What can an Historian learn from playing Cluedo?’ Here is just one of the responses.

WHAT CAN AN HISTORIAN LEARN FROM CLUEDO?

By playing Cluedo, we developed many skills. From patience and persistence to making connections between completely

obscure topics and listening carefully, Cluedo is a whirlpool full of new knowledge. But is Cluedo really just a game that ages 9 – 99 can play? Or is it also a tool for historians and researchers to develop their own skills?

We are curious in Cluedo as we genuinely want to find out who committed the murder because we want to win!

We use patience and persistence in Cluedo, without even realising. When we feel like we are NEVER going to get the answer and uncover the truth, we tell ourselves (unconsciously) to be patient, and sure enough, the answer comes along soon if we persist.

We make connections between people, places and what other people have said, which also means we have to listen carefully as someone might let something slip by accident that might give us a huge insight into the answer. This also relates to the next point:

Keeping up with what’s going on in the game. Otherwise, you could completely lose track.

We definitely learn not to jump to conclusions, as if you do and you are wrong, your whole case will be wrong.

Lastly, we need attention to detail and precision, because you might waste your go completely if you haven’t paid attention to every last little detail.

But, when you think about it, people don’t just use these skills for Cluedo. Historians use them to help uncover the past. But really, are historians only people who call themselves historians? Or is anyone who has ever been interested in finding out more about the past a historian? Maybe the people who are historians professionally have had a bit more experience, but that doesn’t mean we can’t all be historians!

Firstly, historians need curiosity to set them off on their journey of discovery. One example of this is when my mum and I were clearing out my grandfather’s attic after he passed away, when we found his old World War II diary that he wrote in every day when he fought in Tobruk. This sparked our curiosity and we immediately wanted to find out more about this part of the war.

We used patience and persistence when we couldn’t find out any information straight away out of some books or the Internet. But it’s not just us who did that, as people all over the world practice all these skills, especially historians, when they are trying to find out information.

Yet, slowly, we began to make connections between the little things that we read in books and things we had heard off the radio, by keeping up with what’s going in the world through listening carefully!

We began to piece bits of information together, and learnt not to jump to conclusions, like when we turned up to an exhibition about the war at Tobruk to celebrate its anniversary and discovered how wrong we had been in some parts by jumping to conclusions with just a few bits of evidence. So we used the skill of paying attention to detail at this exhibition, making sure we looked carefully at each object.

We started off with a few clues and then discovered a whole part of grandfather’s life that we hardly knew about at all, through doing exactly what a historian would do, which is exactly what happens in Cluedo!

So, historians would learn how to use their skills from Cluedo in a way that could uncover a part of the past, by just playing a board game!

As you can see from the depth of this answer, that’s why we used Cluedo. True, this is a sophisticated response but it was one among many. Most pointed out ‘not jumping to conclusions’ or ‘checking facts‘ or even ‘listening’ were essentials skills that were needed to win the game, or if you were an historian, pose a credible hypothesis. Or, in the case of a detective, crack the case. And that’s where the imaginative play came in…

Crime Scene Investigators: CAIRO

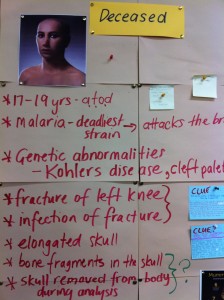

detail from the forensic board

What was once a classroom is now set up with a slab in the centre. Around the edges are groups of desks with notecards and files marked CLASSIFIED. Behind on the wall are a series of boards with images hastily tacked to them. Some have captions that read ‘Deceased’ and ‘Location’ and ‘Suspects’ and ‘Cause of Death’. The students gather nervously around the slab and take in the gold sarcophagus (well, a laminated full size poster of it) that lies before them. At the head of the slab the person they think to be their teacher is lounging, hands in pockets and a strange fedora hat on his head. When he speaks it is not his normal voice but a gruff, bombastic one that is reminiscent of Gene Hunt from ‘Life on Mars’ (sans swearing). ‘I’ve heard from your teacher that you investigators know your way around an unsolved death. You’ve got your work cut out for you on this 3000 year old cold case. Are you up for the challenge? Who or what toppled Tut?’

Teacher-in-Role is a classic play-based method that has been used for decades, particularly in Primary/Elementary classrooms. Besides being a powerful way to introduce drama, role and performance codes to young children, it’s a great deal of fun for all involved – not least the teacher. It is sometimes forgotten that in the *shudder* gamification of education it’s not only the kids that need to be engaged and having fun as they learn. Playing the ‘Chief Inspector’ gave me an opportunity to push the boundaries of communication and keep each lesson fresh. Each student ‘bought’ the conceit that the mean-spirited cranky man was a role and he was good to talk to for some things but the teacher might be better for others. That was when I had to take off the hat and soften the voice. The ‘Chief Inspector’ belligerently demanded evidence and sources to back up their assertions whilst the teacher showed them how to find and cite them so the ‘Chief Inspector’ wouldn’t get mad. Team teaching this was also a great help- to extend the metaphor, we could then easily shift from ‘bad cop’ to ‘good cop’ if there were two of us in the space.

It was also delightful to see how quickly they appropriated the ‘Chief Inspectror’s’ forensic discourse, referring to Tutankhamun as the ‘deceased‘ and using terms such as ‘circumstantial‘ and ‘substantiated with evidence‘. Other students adopted a similar combative tone of voice and revelled in their role as detectives.

From there it was down to the grunt work of investigating the case. Students trawled through forensic data, historical accounts, watched Clickview videos and even ancient religious texts in order to find out what lead to Tutankhamun’s death. They took notes in their Forensic Investigator Notebooks – worksheets that, like their teacher, were also in role! What was so unusual in this whole investigation was that the students had a reason to be learning about the gods, the Nile, the role of the pharaoh outside of having to copy notes or study for a test – what they uncovered about the society might have had some bearing on the case. And it did.

One of the most startling discoveries occurred when the students were investigating education and entertainment in Egypt. Learning that few could write, it came as a surprise to find that Tutankhamun’s wife had written (or at least dictated) a letter that was sent to the King of the Hittites after Tut’s death. The details of this letter can be read here but my, how it fired up the case and shifted the investigation from gangrene as the main suspect back to cold blooded murder.

But it wasn’t all drama games masquerading as history. The fact that Tutankhamun’s body lacked a heart gave the students a significant reason to learn about mummification. This is where a web-based educational computer game (still in beta testing) was employed. Quest History uses the Unity platform to create smooth, effortless time-traveling experiences where students race against the clock to mummify a body under the watchful eyes of Anubis. Sure, it was gross and icky but each student was left questioning the absence of a heart in Tutankhamun’s tomb and some later developed intriguing theories to explain its disappearance.

The Hippo did it

The penultimate stage of the investigation was when each team stood in front of their peers and argued their hypothesis, citing evidence from multiple sources. They needed to be prepared to withstand the withering ire of their colleagues not to mention some significant questioning just like in History faculties the world over. The debates were warm, to say the least, as each group was determined to ‘win’ by disproving each other.

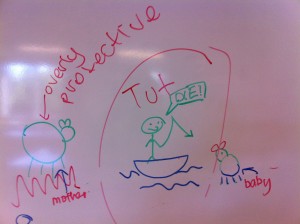

One of the most intriguing theories originally began as a joke explanation on how to structure a persuasive argument. Students successfully argued that Tutankhamun died from the result of injuries sustained in a hunting/fishing accident – he was, as they put it, mauled by an over-protective female hippopotamus. We sat through a dramatic re-creation of the attack and some hastily drawn but nevertheless engaging diagrams that captured the minds of their fellow detectives. Evidence from the tomb including the correct season of his death based on floral offerings found on the body as well as contemporary accounts of injuries inflicted in hippo attacks, were used to substantiate their case. Many students were convinced to the point of putting aside their own hypotheses.

Case closed

After testing their knowledge in the arena of their peers, it fell upon the detectives to submit a final report that argued a cogent case. Whether it was a hippo, a chariot accident, a disappointed wife, cerebral malaria or a power hungry vizier that killed the boy-king was not really the issue nor what was being learned. As Isabelle wrote in the quote that opened this posting, the game-like exercise was one that developed independence and confidence in challenging what is put before us- essential skills for any game or, indeed, for life.

Cluedo gave us the way in to play with the idea of becoming a detective. It highlighted the key skills we needed to employ and reminded us to stay open-minded yet critical of what the evidence seemed to suggest. And it was an enormously engaging eight weeks of fun with not a single badge awarded.

Next term we introduce Geography using the TV series ‘The Amazing Race” and a National Geographic board game called ‘Expedition‘. Get your passports ready, Year 7. Time for take-off.

Leave a Reply