‘Most men have always wanted as much as they could get;

and possession has always blunted the fine edge of their altruism.’

~Katherine Fullerton Gerould

‘It took longer to make it stronger‘ was a phrase used in the last blog post in this series to indicate the value of engaging students in the construction of a Player Charter for a school Minecraft server. The time to refine the Charter worked to galvanise interest in creating not only a safe space for others to build and play but it also highlighted humanistic ideals of respect and fairness. The lengthy research project my partner teacher and I conducted concluded that game based learning spaces were ideal for developing skills in collaboration, connection, negotiation and creativity. With our school’s executive on board too, we were ready to open the ports to players.

We were all set to open the server to a core trial group of 10 plus our senior school mentors who had worked with us for 18 months. The wider Minecraft Community at school were excited. Our enthusiasm was electric. The spawn point was ready to welcome the new year 5 students into its light filled hall. The orientation dungeon was filled with traps and treasure. The parent and student signed copies of the Charter were speedily returned to us. We opened the Server…and it all went ‘wrong’.

This blog post recounts some painful lessons on how our idealism came to grief as well as how we are building the community , block by block and quest by quest through employing Acronyms, highlighting Altruism and opening up to Adventure.

Lesson 1: The need for Acronyms

What follows is a simulated, but accurate in tone, transcript of our first few sessions with the girls. Imagine players dispersed about the room, engaged solely with their screens. When reading the script, please adopt a nasal righteously indignant whining voice – the kind that often is used when reciting the pre (and post) teen mantra of ‘It’s not fair!’. Alternate that with a frustrated shouting and you have the general sense of these early sessions.

PLAYERS run to a table, ignoring each other and login.

A few minutes later...

PLAYER 1: Who took my emerald! I stole that from an NPC village! Give it back! PLAYER 2: I need food. Fooood! PLAYER 3: builds a house quietly by herself PLAYER 4: Zombie! Zombie! Zombie! PLAYER 1: Don't go into my house. That's for me and (name omitted) only! PLAYER 2: Food! Food! Who has beef? Gimme food!I'm on one health! PLAYER 3: crafts tools by herself and hides them in a buried chest. PLAYER 4: Aaah! Creeper! Creeper explodes *Boom*

What were we expecting – immediate harmonious collaboration? Recalling the words of a Head of School I respected and valued deeply, this was an important F.A.I.L – a First Attempt In Learning how to create an effective play space. Rather than become dispirited: or worse, authoritarian, we employed two techniques that also involved acronyms to shift the discourse and encourage connection.

Acronym 1 : AAA or Triple A

To encourage connection with each other before connecting with the play space, we established a quick but effective protocol before logging in. Students, mentors and staff sit together in a circle and we go around responding to three brief prompts.

- What’s been AVERAGE today? (by that we mean ‘dull’, ‘irritating’, ‘boring’ or ‘meh‘ over the course of the school day.) Curiously, this often prompts comments of agreement, clarification or even elaboration. Sometimes laughter.

- What’s been AWESOME? (Usually they say ‘Coming to Minecraft!’ so we allow elaborations and brief comments on the successes and joys of the day.)

- What’s on the AGENDA? (By this we mean what do you want to achieve today? Build? Explore? Collaborate? Craft?) WE’ve seen this inspire others who might lack an idea on how to proceed or even instigate a cooperative build.

Acronym 2: T.H.I.N.K

To encourage rather than enforce more ‘connecting’ or compassionate communication, we have another acronym that we are beginning to share more widely in the school context as a means of shifting the way we talk, type and text.

By referring to THINK before, during and after positive and problematic communication to draw attention to how the communication ‘feels’. How did you know that person griefed your build? What evidence do you have? How does it feel when someone inspires us to be better at something? How does it feel to hear kind words about your builds? Did someone help you to craft something and how was that for you? How was that for the helper? By highlighting our communication with meta-language, we are experiencing a significant tonal shift in our communication whilst we are playing. Also, drawing attention back to the Chat feature really reduces some of the more problematic discourse.

This is the sort of communication we are getting now.

PLAYER 1: Does anyone have any spare iron? PLAYER 4: Sure, I've got some. How much? PLAYER 2: I've been farming. Anyone want wheat? PLAYER 3: Hey, you dropped your boots. Here they are. drops boots PLAYER 4: Zombie! Zombie Zombie! PLAYER 3: uses bow and arrow to kill the zombie for PLAYER 4 PLAYER 4: Thanks! PLAYER 1: Let's start making shops. Who wants a cake? ALL PLAYERS: ENDERMAN! Aaargh!

Lesson 2: Valuing Altruism

We build connections with sharing our stories as well as sharing our resources but the fact is, do most Minecraft players value sharing? Do they build for the common good or for their own sense of achievement? Are these mutually exclusive?

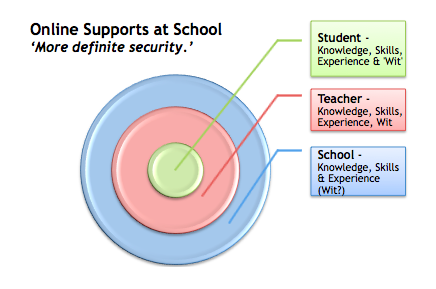

To encourage greater interconnection and foster a community spirit we have our Schoology Group where images of our builds, discussions about potential design challenges and the posting of entertaining Youtube videos occurs. But we also have the fantastic customisable Game Engine, 3D Gamelab in which we have crafted a series of quests that celebrates individuals efforts but pays even greater emphasis on actions for the good of others.

Players level up by completing community quests and personal ones, though the points awarded are clearly skewed towards altruistic endeavours. As a rule of thumb – if it helps more people its worth more points. As students progress from DREAMER through multiple levels including CREATOR, MASTER CRAFTER, SUPER HERO and eventually SOURCE OF ALL KNOWLEDGE they gain in-world gear and increased abilities. (We are still ironing out the rewards at each level but I’m sure all the Super Heroes want to be able to fly!)

Players level up by completing community quests and personal ones, though the points awarded are clearly skewed towards altruistic endeavours. As a rule of thumb – if it helps more people its worth more points. As students progress from DREAMER through multiple levels including CREATOR, MASTER CRAFTER, SUPER HERO and eventually SOURCE OF ALL KNOWLEDGE they gain in-world gear and increased abilities. (We are still ironing out the rewards at each level but I’m sure all the Super Heroes want to be able to fly!)

By adding value to altruism we are hearing very different ideas from the players – Can we earn points for creating shops? She saved me from that skeleton, she should be rewarded. Have you seen the farm we made, its awesome! (Badges from symb.ly)

Lesson 3: Opening up to Adventure

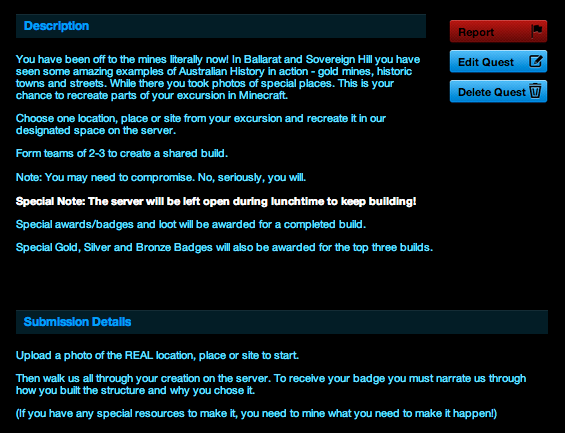

The players by this point had structures in place for them to choose their own direction and work alongside others. We had protocols to assist in refining our communication, yet they lacked a common goal. As it turned out, their excursion to the 1850s Gold Mines of Ballarat, Victoria prompted an interaction between myself and one of the year 5 girls who wondered if she could use Minecraft to make a model of something she saw. This prompted our first design challenge.

Chaos reigned again until the design teams met with the senior mentors armed with large sticky notes and pens. Designs were drawn up and discussions were had. IT was fascinating to watch the shoddily unsymmetrical builds get revamped after only twenty minutes of face-to-face discussion and drawing.

After three weeks and multiple sessions, including some lunchtimes, the students constructed a number of intriguing designs. Again it must be noted that our Minecraft server is set to Survival (at their request) in order to provide greater challenge and reflect the reality that not all resources are infinitely available. They needed to survive the nights, go on scouting parties to gather resources and keep each other live during that time. At the end of this period the students walked us through the designs, some of which were incomplete. This video (sadly unedited, so if you have a spare 23 minutes you may find them well spent by watching this) was recorded to show to the Year 5 teachers who were unable to attend but were keen to see what was possible.

The winning design recreated the aptly named Victory archway in Ballarat (shown below) which they constructed in sandstone. The team who constructed this was rewarded with 50 XP each and a full set of diamond armour.

Play’s the Thing – Endgame

We are still learning what is possible with Minecraft. We continue to explore the shifting boundaries of freedom and control when creating play spaces for young people. Thankfully we have the experience and insight of our senior school mentors to assist with not only the technical aspects of running a server, but also the broader vision for its implementation. Thanks to them we have a Player Charter to guide the members towards forging a creative and collaborative community that values altruistic endeavour as well as self-expression. By sharing protocols such as the AAA and THINK acronyms, we are bringing awareness to the very building blocks of community – the content and tone of communication. Through inventing contexts for play in consultation with the players, we ensure their commitment provide opportunties to celebrate their ingenuity.

What is ahead for us? Look out for some pixel art galleries or our Machinema challenge where teams are given generic dialogue and select a genre of film to recreate – props, sets, skins and all! Or the UN-tervention challenge where rather than being raided, an NPC village needs to be repaired, maintained and defended from hordes of zombies.

Postscript

This series has drawn its title from Hamlet’s words ‘The play’s the thing/ Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the King.” from Act II, Scene 2. Perhaps we can be permitted a slight modification of this quote for use in the context of Minecraft. For in this kind of creative, reflective ‘play’ we may in fact, ‘build’ the conscience – the altruistic, self-reflective faculty – of the kings, queens and leaders of the future.

Or we could just go to the Nether and hack into some zombie pigmen. Up to them I suppose.

Recent Comments